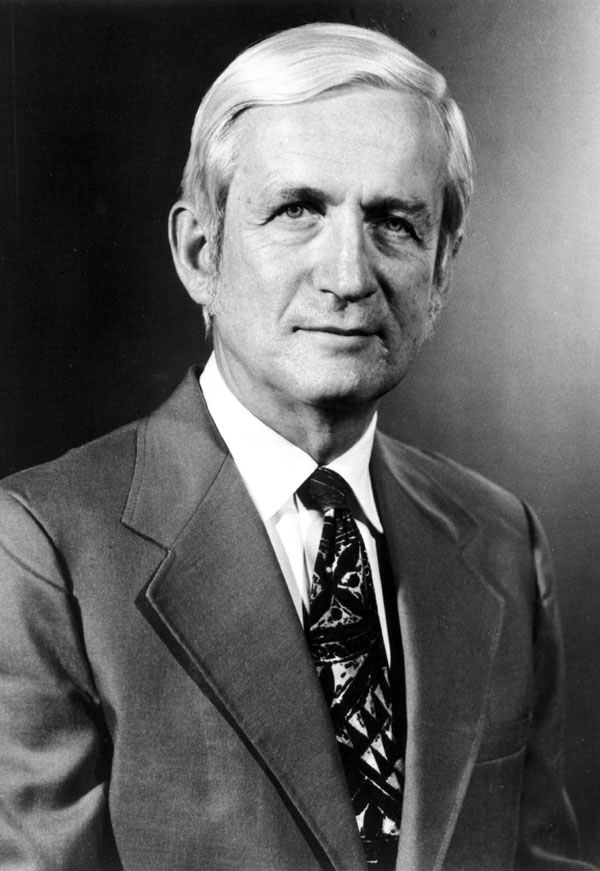

اکثر کسایی که دوره لیسانس فیزیک رو پشت سر گذاشتن قریب به یقین اسم گریفیث رو شنیدن. در خیلی از دانشگاههای دنیا کتابهای الکترومغناطیس و کوانتوم گریفیث رو برای دو ترم متوالی تدریس میکنند. همینطور کتاب آشنایی با ذرات بنیادی گریفیث نه تنها یکی از بهترین منابع برای دانشجوی کارشناسیه که جزو اولین کتابهای آموزشیه که برای اون مخاطب نوشته شده. خلاصه که گریفیث شخص نامآشنایی هست در آموزش فیزیک.

دو سال پیش، پروژه تاریخ شفاهی امریکا مصاحبهای با گریفیث کرد که مثل اکثر مصاحبههاشون خیلی خوندنیه. برای من که همیشه برام آموزش مهم بوده و در دانشگاههای مختلف از تدریس بد آدمها رنج بردم، دیدن نظرگاه کسی مثل گریفیث خیلی مهمه. بخشهایی که از این مصاحبه برام خیلی جالب بود رو اینجا میذارم. اصل این مصاحبه در این نشانی در دسترسه.

گریفیث، مثل خیلی از فیزیکدونهای دیگه از یک خونوادهای میاد که پدر و مادر هر دو استاد دانشگاه بودن اما نه فیزیک. خودش میگه به فیزیک علاقهمند شد چون که حس رهایی داشته:

I found it very liberating, and history very stifling. So, that, I think, is what confirmed me in physics. … I knew I was going to be a scientist and a physicist from a very early age for no terribly good reason.

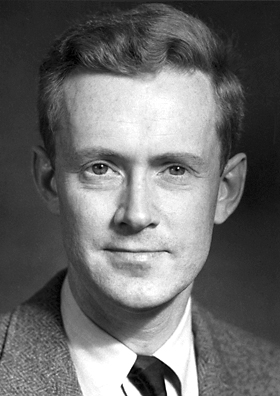

در کل آقای گریفیث نکات قابل توجهی در مورد آموزش و پژوهش در فیزیک رو گوشزد میکنه و در کنارش هم ماجراهای جالبی تعریف میکنه. از این که وقتی جولیان شویینگر توی هاروارد بوده نمیذاشته کسی جز خودش نظریه میدانهای کوانتومی درس بده برای همین اون لکچرهای معروف سیدنی کلمن که امروز هم در دسترسه در واقع به زمانی برمیگرده که شووینگر از هاروارد رفته بوده.

Schwinger insisted that only he could teach quantum field theory. So, it was not until Schwinger left Harvard that Coleman was able to teach this now-famous course.

[with Carl Bender] We were both in the field theory course together, and after every lecture we would get to either his apartment or mine, and rewrite our lecture notes from Schwinger’s lectures, because they were brilliant. They were also very difficult, and we wanted to have perfect lecture notes for this course.

گریفیث تعریف میکنه که وقتی نتایج ابتدایی شتابدهنده کمبریج منتشر شد، اونا با پیشبینیهای نظریه الکترودینامیک کوانتومی تفاوت داشت. اون موقع، سر کلاس نظریه میدان شووینگر، کسی در مورد این مغایرت میپرسه و شووینگر در جواب میگه لابد واسنجیشون مشکل داره. سه چهار ماه بعد، وقتی که در کمبریج نتایج رو بازبینی میکنن متوجه میشن که با درست کردن واسنجی شتابدهنده، دادههای تجربی با نظریه همخونی داره!

“What do you make out of the latest results out of the Cambridge Electron Accelerator?” And Schwinger, who was always irritated when somebody asked a question, sort of looked at his watch and said, “Well, I think they have problems with their calibration.”

به هر تقدیر شویینگر هم فیزیکدون تراز اولی بوده. آقا، همراه فاینمن برنده جایزه نوبل به خاطر کارشون روی الکترودینامیک کوانتومی شد. درسگفتار الکترومغناطیس شویینگر یکی از عمیقترین و متفاوتترین کتابهایی هست که آدم میتونه برای عمیق شدن روی موضوعات مختلف بخونه. اما خب شخصیت شووینگر، بر خلاف فاینمن، بسیار ساکت و کمی تا قسمتی نامهربون بوده.

برای زندگینامه شووینگر به این کتاب نگاه کنید.

ما در دانشگاه بهشتی هم از این داستانها داشتیم که تا فلانی هست نباید بهمانی درس بیسار رو بده. مثل اینکه این ماجرا در محیطهای خیلی حرفهای هم بوده و هست. ولی خب اونجا رقابت بین غولها بوده و اینجا بین آدمهای دوپا. این ماجرا خیلی جالبه چون کلاس کلمن در هاروارد تبدیل به یکی از بهترین کلاسهای درس میدانهای کوانتومی میشه جوری که هنوز هم که هنوزه آدمهای زیادی ویدیوهاش رو میبینند و درسگفتارهاش رو میخونند. خود کلمن هم فیزیکدون درجه یکی بوده که با این که زیاد علاقهای به تدریس نداشته اما وقتی این کارو میکرده، به خوبی از پسش بر میاومده و تجربه کلاس درس برای دانشجوها خیلی خوشایند از آب در میاومده.

Tony Zee had gone to Coleman and said, “I would like to work with you. What would you suggest as a research problem?” And Coleman said, “If I had a research problem, I would work on it myself,” and sent him away.

گریفیث در مورد شلدون گلشو (برنده نوبل فیزیک همراه با عبدالسلام) میگه که:

He is an amazing guy with an idea every minute. Most of them garbage, but every once in a while, one that’s fantastic. He and Coleman made a perfect combination, because Coleman was the opposite. He could demolish any idea. You’d tell him some new idea, and he would immediately see ten flaws in it.

گریفیث که الان استاد بازنشسته کالج ریده، فضای رید رو به خاطر اولویت آموزش بر پژوهش خیلی دوست داره. با اینکه هاروارد بوده و فرصت بودن در محیطهایی که بیشتر تمرکزشون روی پژوهش بوده رو داشته انگار تلاش کرده خودش رو از فضای رقابتی چاپ مقاله دور نگه داره و تمرکزش رو بذاره روی یادگیری.

I like to publish. I flatter myself that I publish when I think I’ve got something useful to say that would actually benefit somebody else. I’ve never felt, at Reed, obliged to publish because that’s part of my job or something.

موقعی که از دوران تحصیلش توی هاروارد میگه، اصلا از کیفیت کلاسهای درس راضی نبوده:

My first two years at Harvard were a wasteland in physics, as far as quality of teaching is concerned. I had a lot of teachers there who frankly would not have lasted a semester at Reed, but they were fine at Harvard because they were, or had been, significant researchers or whatever.

The instruction at Harvard was so terrible, especially in the first two years, but actually even in the third year. I remember courses that were really awful. I did then encounter Ramsey, and he was great, and my senior year, Purcell. But learning physics was not a happy experience at that point for me. I liked the subject itself once I understood it, but I remember going to lecture after lecture and not understanding a word that this turkey

was talking about.

نکته خیلی مهمی که گریفیث اشاره میکنه اینه که وقتی کلاس درس به خوبی برگزار نشه خیلی از دانشجوها ممکنه فکر کنند که مشکل از اونهاست و خودشون رو سرزنش کنند که توانایی یادگیری ندارند، در صورتی که بیچارهها گناهی ندارن و مقصر استاد درسه:

Now I can look back on it and say, that was just lousy instruction. It was not my fault.

But the process of learning with lousy instructors is grossly inefficient and unpalatable. I sometimes think that I learned the subject better at Harvard than most of the students at Reed learn the subject, either because I taught myself or I learned it from hashing things out with fellow students, or whatever.

خلاصه هر چیزی که یادگرفته از صدقه سر تمرین زیاد و پیگیریهای خودش بوده نه کلاسهای هاروارد.

It was not because the teaching was good, but precisely because I had to fight for it, I think I learned it ultimately better. That’s a horrible thing to concede for someone who’s devoted his life to teaching, but I think somehow, if it works, the sort of bad teaching method probably is effective and beneficial.

به گفته گریفیث، توی هاروارد اگر کسی هم احیانا خوب درس میداده بر حسب اتفاق بوده! انگار که اصلا خوب درس دادن توی خونشون بوده نه اینکه تلاشی بکنن. مثلا کسایی مثل سیدنی کلمن، نورمن رمزی و ادوارد پرسل معلمهای خارقالعادهای بودن اما بر حسب تصادف نه چون هاروارد اونها رو به خاطر تدریسشون ارتقا میداده یا این جور چیزها. البته گریفیث میگه ممکنه در دورههای بعد بهتر شده باشه چون وقتی پسرش میره هاروارد مثل اون شکوه و گلایه نمیکنه از اوضاع تدریس. اما خب به وضوح خیلی چیزها در این مقایسه متفاوته، از جمله نگاه گریفیث به امر یادگیری و آموزش.

قریب به یقین شما اسم کتابهای دوره فیزیک برکلی رو شنیده باشید. اد پرسل کتاب الکترومغناطیس اون مجموعه رو نوشته. گریفیث معتقده که پرسل یکی از بهترین معلمهایی بود که در هاروارد داشته. گوشه ذهن من اما همیشه یک سوال باز بود که کتاب پرسل خیلی خوبه ولی نه برای شروع. ولی همیشه خودم رو این جوری توجیه میکردم که خب لابد بچههایی که هاروارد یا برکلی هستن خیلی بهتر از منن برای همینه که من احساس راحتی نمیکنم با کتاب پرسل. به عبارت دیگه، مشاهده من در دوران تحصیلم این بود که زمانی که دانشجوی لیسانس برای اولین بار درس الکترومغناطیس بر میداره خیلی حس راحتتری داره وقت کتاب گریفیث رو برای شروع انتخاب کنه تا پرسل. نکته جالب اینه که گریفیث هم به این مسئله اشاره میکنه! تعریف میکنه زمانی که معلم حل تمرین درس الکترومغناطیس پرسل بوده مدام این نکته رو به پرسل گوشزد میکرده که سطح این کلاس بالاتر از لیسانسه. اما خب، با این که خود پرسل هم شکایتهای مردم رو میشنیده اونا رو مزخرف میدونسته و توجه نمیکرده:

Purcell is the greatest ever, but that’s at a more elementary level. … He had been getting complaints from people. They said, “That’s a beautiful book. Maybe you can use it for honors students at Harvard, but you can’t use it for most students.” And Purcell always said, “That’s nonsense. This book was written for every physics student.”

مشکل این نبوده که کیفیت کلاس درس بد بوده، یا بار ریاضیات کلاس پرسل زیاد بوده. نه! دانشجوی لیسانس در اون مقطع هضم مفاهیم فیزیکی رو جوری که پرسل درس میداده براش سخت بوده:

I went to every single one of his lectures, which were spellbinding. They were brilliant lectures, and his demonstrations were fantastic. … It’s not that it’s so sophisticated. Mathematically, it’s not very sophisticated, but physically, it’s very sophisticated. It’s very demanding of a student. The kind of student who wants to solve the problems by paging back and finding the relevant-looking formula, but not actually reading the chapter, it’s a hopeless book for them. You have to read some chapters two or even three times.

اما سرانجام یک بار که پرسل به دانشجوهای غیرممتاز درس میداده و گریفیث معلم حل تمرینش بوده، اعتراف میکنه که بله، این کلاس برای همه دانشجوها نیست. سنگینه! خلاصه با این که به نظر گریفیث کتاب پرسل خیلی خوبه، اما صادقانه بخوایم بگیم برای دانشجوی تازه وارد نوشته نشده. علت محبوبیت کتاب الکترومغناطیس گریفیث هم اینه که محتوای استاندارد خوش هضمی رو برای دانشجوی سال دو یا سه فراهم میکنه. هر چند که موفقیت کتابش برای خودش کمی فرای انتظارش بوده!

… Purcell’s is the greatest textbook — maybe the greatest textbook ever written on any subject in physics. But mine is much more standard, junior level. Maybe a little bit clearer, maybe a little bit more user friendly, but basically, I’ve been astonished at how successful that book has been. I don’t understand it, frankly.

در مورد نوع درس دادن مکانیک کوانتومی هم گریفیث نظرات قابل توجهی داره. مسئله اینجاست که چون نظریه الکترومغناطیس (حتی الکترودینامیک) کماکان جزو حوزه کلاسیک فیزیک حساب میشه چندان تفاوت نظری وجود نداره که از چه مباحثی شروع به تدریس کنیم و به چه رویهای پیش بریم. اما مکانیک کوانتومی این جوری نیست. کتابهای مختلف کوانتوم گاهی با سیر تاریخی پیدایش نظریه مکانیک کوانتومی پیش میرن و گاهی رهیافتی خیلی مدرن دارن.

آزمایش اشترن-گرلاخ’ آزمایشی در فیزیک است که نشاندهنده انحراف کوانتومی ذرات در میدان مغناطیسی است

این آزمایش نشان میدهد که الکترونها ذاتاً ویژگیهای کوانتومی دارند، و این که چه طور اندازهگیری در مکانیک کوانتومی روی چیزی که اندازهاش میگیریم تأثیر میگذارد.

یادمه اولین بار که درس مکانیک کوانتومی در بهشتی داشتیم، استاد ما با یک کتاب جدید به اسم مکینتایر اومد سر کلاس و خیلی خوشحال بود که این کتاب خیلی مدرن نوشته شده و فوقالعادهس برای تدریس. کتاب مکینتایر در واقع نسخه کتاب ساکورایی بود برای دانشجوی لیسانس. یعنی ب بسمالله کتاب، آزمایش اشترن- گرلاخ و مسئله اسپین بود. نتیجه کلاس برای من چیزی نبود جز اتلاف وقت چون اصلا احساس یادگیری نمیکردم. بخشیش به خاطر استاد و عدم تسلطش به موضوع بود و بخش دیگهش به رهیافت کتاب مکینتایر برمیگشت. کتاب ساکورایی کتاب خیلی خوبیه و دانشجوی تحصیلات تکمیلی زمانی باهاش روبهرو میشه که اصول رو یک بار در لیسانس دیده و مسیر تحول فکریش خوب ساخته شده. برای همینه که ساکورایی به جای مسیر تاریخی، با یک رهیافت مدرن شروع میکنه و قصه رو کلا جور دیگه بیان میکنه. جوری که صفحات تاریخ رو جابهجا میکنه و یک روایت جدید تعریف میکنه. اما برای دانشجوی لیسانس، درک مسئله اسپین، به عنوان یک مفهوم کاملا مدرن ساده نیست. چه طور میشه به کسی که شهود روزمرهش درگیر مسئله چرخش زمینه، اسپین رو توضیح داد و بگی این همونه فقط نمیچرخه؟! خلاصه من اون کلاس رو نرفتم و کتاب گریفیث رو شروع به خوندن کردم و همه چیز برام روشن شد.

How do I go into class on the first day and say, imagine a system in which there are only two possible states, or linear combinations of those two states, and having students look at me as though I was the man on the moon, or something?

When you’re coming out of classical mechanics, unless you go to something like classical optics and talk about polarization — that’s a system that has two different linear polarizations, and you can have linear combinations of those – but what’s the connection between that and mechanics? It’s awkward.

I can’t stand popularizations of quantum mechanics that love to say, well, a particle is neither a wave nor a particle. The electron behaves sometimes like one and sometimes like the other, and there’s no coherent way to picture it. I don’t like that because if somebody has not studied quantum mechanics, I think that it’s mumbo jumbo.

البته توضیح هم میده که چرا روشی که خودش برای نوشتن کتاب مکانیک کوانتومیش پیش گرفته رو ترجیح میده:

In the case of quantum mechanics, there are radically different ways of presenting the subject, and mine is one take on how to present quantum mechanics, the one that I happen to feel pedagogically most comfortable with.

Mine is based on position space quantum mechanics, wave functions, starting with the Schrödinger equation. I was determined that the Schrödinger equation would appear on the first page of my book, and it does. But the wave function, psi, lives in Hilbert space. It is mathematically a subtle and tricky kind of object, which you sort of sweep under the rug, but eventually it’s going to come up and bite you. … I’ve never dared to teach it that way myself because the motivational problem strikes me as being very, very tricky.

روش گریفیث در درس دادن فیزیک تلاش برای واضح بودن و از ساده به سخت رفتنه:

There’s no reason not to be as clear and as accessible as you possibly can. So, I’ve always, in teaching, favored the simplest possible way of explaining something. … Let’s start out with [ … something] very concrete and non-abstract, and then ascend to the higher levels of abstraction later in the subject, not at the beginning.

به طور کلی اما گریفیث نسخهای نمیپیچه که بهترین روش تدریس فیزیک چیه:

I do agree that there are lousy ways of teaching. I have already confessed that I experienced a good deal of that. I have theories about what makes for lousy teaching. I don’t know what makes for great teaching. I’ve seen lots of different great teachers, and I would hate to have to give you a prescription for what makes good teaching of physics. I was in some respects ambivalent

I learned very quickly in my teaching career that a lot of my students could think a whole lot better than I could, or at least a whole lot faster than I could. What I was doing is, I knew something, understood something about the physical world that they didn’t, and that they wanted to know.

So, my business as a teacher was not to teach them how to think, although in some vague, indirect sense, maybe that’s true, but I was going to explain things so that they would come to understand basic principles of physics. I have a very un-exalted notion of what my role as a teacher is: to explain things in as efficient and as appetizing a way as I possibly can.

So, my parents, again, subscribed a little bit to the notion that a teacher is sort of like a drill sergeant or a gymnastics instructor. Your business is to make these students jump through a bunch of flaming hoops or something. I don’t know; that sort of rubs me the wrong way. I’m trying to liberate students from perhaps incorrect intuitions, or simply from ignorance.

توی مصاحبه یک جایی گریفیث اشاره میکنه که یک رسمی عجیبی وجود داره که هر سال معلمها و اساتید اشاره میکنن که آره کیفیت دانشجوها اومده پایین و قبلا این جوری نبود و اصلا دیگه کسی براش مهم نیست و از این حرفا. این خیلی عجیبه چون از زمان سقراط و ارسطو هم این حرف و نقلها بوده و اگر واقعا همیشه کیفیت دانشجوها رو به زوال بوده قاعدتا نباید دیگه چیزی به ما میرسید. توجیه این ماجرا هم چیزی نیست جز فراموشکاری آدمها و خطاهای شناختیشون!

It’s a sort of weird psychological phenomenon. You remember the wonderful students, and you blissfully forget the not so wonderful students. So, your memory is always a rosier past than the present.

به نکتهای گریفیث اشاره میکنه که خیلی به دل من نشست. حقیقت اینه که از وقتی که من اومدم دانشکده علوم کامپیوتر دانشگاه آلتو، به این مسئله زیاد فکر میکنم که چرا آدمها این جا اصلا علاقهای به صحبت کردن در مورد علم ندارن. اکثر آدمها در مقطع تحصیلات تکمیلی همه تلاششون رو میکنن که در زمانهای استراحت یا ساعات به اصطلاح خودشون غیر کاری راجع به علم – کارشون – صحبت نکنن. دلیلشون کمی قابل قبوله چون بالاخره استرس و فشار کاری زیاده و آدمها تلاش میکنن خارج از کار، مفری برای آسودگی خاطر پیدا کنن. اما از طرف دیگه، به نظر من مهمترین رکن یک محیط علمی، شور و اشتیاق آدمای اون موسسه به پرداختن به علمه!

… All liberal arts colleges claim that their students are very studious and academically committed and all that, but Reed is the only place, including Harvard, where I’ve found this to be actually true. I remember one of my first experiences at Reed was down in the locker room, in the gym. I’m a swimmer, so I was down there to go swimming, and realized that the student conversation in the locker room was all about their Hegel lecture that morning.

At Trinity, it was considered absolutely rude to talk about your classwork outside of class. In the lunch hall, you’re supposed to talk about fraternities and the progress of the football team, you know? But at Reed, everybody’s focus and attention were their academics. It’s a little bit overly precious sometimes, but it’s so much more refreshing, especially for a teacher, than the opposite.

گریفیث معتقده تعادل بین تدریس و پژوهش خیلی مهمه و دلیلی نداره که این همه موسسه با این حجم از پژوهشگر فقط در زمینه چاپ مقاله پیشتازی کنند.

First of all, I think, in general, the world would be a better place if about 75% of all publications had never been published, because there’s this, to me, childish emphasis on publication — publish or perish, you know?

People feel compelled to publish garbage, and they do. Most publications in physics, we would be better off if they had not been published. You say, well, everybody’s making an incremental change and improvement, or something like that. Well, that’s not true. What they’re doing is clouding the works, by and large.

Nicholas Wheeler, who’s, second to Coleman, the most brilliant physicist I’ve ever known. He does not publish and will not publish. He writes these incredible monographs. In the old days, he would literally calligraph them himself. Beautiful — he’s a genius at taking some subject in the literature, writing it up in his own words, so that what had been this convoluted, complicated, murky subject, and it comes out as this beautiful, crystal-clear thing in his hands. Nowadays he types them all, and they’re actually available on the web.

But he will not publish anything. Is it original? No, in a certain sense, it’s not. He’s taking something that’s in the literature, and as I say, cleaning it up. Polishing it. I think it’s not research. It’s not, at least, original research, but it is a contribution of the highest order. But it wouldn’t satisfy a modern dean — he wouldn’t have survived a year at a research university because he refuses to publish this stuff.

In the physics department at Reed, at least, we like to think of the senior thesis project as a research project in which the student is 100% in charge. This is a myth, but it’s a good myth. … we like to pretend that the student has input and ownership of all aspects of it.

در ضمن، آقای گریفیث چندان علاقهای به ترویج علم به زبان ساده و چیزهای این شکلی نداره! میونهش با کتابایی مثل تاریخچه زمان هاوکینگ خوب نیست و به نظرش اگه کسی میخواد چیزیو یادبگیره باید اصولی یادبگیره. وظیفه خودش رو در توضیح دادن چیزها به بهترین شکل میدونه اما در قالب حرفهای نه کتاب قصه:

I don’t like popularizations of physics. Things like Hawking’s [A] Brief History of Time, that talk about physics but don’t actually teach you to do it, and I think very often give you a very misleading — you know, because they want to use intriguing terms, and precisely want you to be amazed by the physics rather than understand the physics. That kind of rubs me the wrong way.

I wanted to write a book that would be for non-science people, but teach them actually, with a little bit of nuts and bolts, about what’s going on in the subject. Not the speculative supersymmetry, but real, established physics. But because I don’t believe you can understand that stuff without doing occasional problems, I sprinkled through the book problems, and I was told right at the beginning, you put problems in there with numbers and equations, nobody’s going to read it. But I wanted it to be an honest introduction to the subject.